L’esprit Perdu: Postmortem

I’ve been eager to write this post for the past few months.

My latest music work, L’esprit Perdu (shameless plug) - which is French for “The Lost Spirit” - is many things: a reintroduction to composing, an abandonment of creative limitations, an exploration of my own creative process(es), a forward-facing exploration, a revisitation of what I enjoy writing, and a revival of the composer in me.

The narrative idea of L’esprit Perdu is the ethereal journey of the Wanderer trekking through a remote landscape in search of a fabled ancient temple said to grant exhilarating peace and contentment.

Burnout: Becoming Lost

After completing the 10-month graduate school program in the summer of 2018, I was underprepared to no longer be a student and lose the structure that schooling provided for my life up until that point. I was burned out. Over the span of several months, I realized that I was exhausted creatively, motivationally, and (to an extent) emotionally.

In graduate school, there were a few compositional practices expected of us to 1) standardize and streamline the presentation of our work to our advisor, and 2) develop habits for scoring films quickly and efficiently.

First, we needed to create a 3-line sketch of our composition, which included a single staff on top for the melody and a grand staff below for harmony and its rhythmic patterns. The purpose of the 3-line sketch was to keep our ideas simple and easy to edit from the beginning. Once our sketch was approved, we could then begin orchestrating: taking the sketch and applying it to the instruments available to us for the given project.

I internalized the 3-line sketch process as the right way and the only way to compose music. After graduating, the method felt limiting to me while, at the same time, trying different methods made me think I was composing wrong. Not a 4-line sketch. Not a 7-line sketch. Only a 3-line sketch.

So, in the fall of 2018, months after graduating, I slowly and silently set music aside. Not as a conscious decision; it just faded, like day turning to night.

During the following years, I wanted to want to compose, but I just plain did not want to compose. There were a few moments when I touched back on it, but it never stuck. Because I wasn’t ready for it. I missed composing. I missed wanting to compose.

In 2022, I faced a number of consecutive hardships both personally and professionally. Midway through the year, I realized that a majority of my creative efforts had been focused on what I thought others want, when I should be focusing my creativity on what I want. In the summer of 2022, I began to feel a tug inside of myself. A soft but certain whisper in my core: “You should write a piece of ambient music. You like listening to and writing that. When you’re ready.”

(Re)Discovering My Muse

While in my undergraduate orchestration class, I had the opportunity to orchestrate Claude Debussy’s “The Girl with the Flaxen Hair” for woodwinds, harp, and strings. It was a fun project, and shortly after I bought a book of Debussy’s piano music with the intent of orchestrating more of his work. I never did, and the book sat among my other music books, each pulled as reference material when needed.

The first step I took towards creating what would become L’esprit Perdu was looking through the book of Debussy’s music. I listened to a variety of his works: “Reverie”, “Hommage a Rameau”, “La plus que lente”, “Reflets dans l’eau”, and about a dozen more. Certain pieces spoke to me more than others, and I made notes of which pieces I found more evocative - I also grouped pieces together based on their emotion and general character (playful, dreamy, sullen, etc.).

Ultimately, two pieces stuck out to me the most: “Pagodes” and “La cathédrale engloutie.” Listening to each of these works created distinct images in my mind that I could not ignore.

“Pagodes” was written after Debussy heard an Indonesian gamelan performed at the World Fair, and his piano work reflects the far-east influence. In my mind, I imagined rocky mountainscapes lightly peppered with Chinese pine trees, valleys of lush foliage, and hanging layers of mist.

“La cathédrale engloutie” had a similar effect on me. The piece was written about a Breton myth of a sunken cathedral that, on clear mornings, rises from the water and the sounds of bells and chanting can be heard across the waters. Listening to this piece sparked my imagination. I pictured the landscape from “Pagodes” and added the echoes of the bells across the imagined valley.

I separated and wrote down the melodies from both pieces, and did the same with the chords. These transcriptions were then used as reference material for the piece, along with some of my favorite ambient works written by other composers.

Exploring My Process

In my supplies, I had an Archives brand 18-stave, 64-page blank score book waiting to be used. This was a wonderful opportunity to finally use it. The music I had in mind would use some non-standard notation, specifically for the more ambient sections where meter wouldn’t be used and with the inclusion of sound effects, so writing the piece first with pencil and paper felt right.

Archives 64-page, 18-stave compositional playground of bliss.

One of my initial goals was to abandon the 3-line sketch. Especially for the work in mind, a 3-line sketch would have been too limiting to include melodies, chords, sound effects, and notes to myself about instruments. I opted for a 6-line sketch: two melody staves, a grand staff, a bass staff, and a staff for sound effects. I’m glad I made these decisions, because they lead to the creative freedom I had been needing.

An example of the 6-line sketch.

The decisions also lead to a few important lessons about my own process.

A bad habit I tend to have with creativity is not drafting or iterating ideas before trying to create a finished work. By starting with the paper/pencil sketch of the music with the plan of eventually needing to enter the music into notation software, I was forced to abandon the belief that what I was writing would be the final result. I had to wrestle with this while writing it by hand, because it’s such a deep-rooted habit, but I powered through and continued to write it out.

Something I should have committed to right away was the use of key signatures. I did not use them until about two-thirds through the handwritten draft, and this made my process more and needlessly difficult later on when I entered the music into notation software. The music became confusing to read, because I would lose track of the current key and when a new key would take over. An important lesson for myself going forward.

A few orchestration notes to myself. Whether or not I keep them later in the process is a topic for another day.

Relatedly, I made a similar mistake with the staves. Specifically in the two melody staves, I flip-flopped orchestration notes throughout the piece. For example, at one point I had noted a melody in the first staff to be played by the erhu. Later on, I noted the erhu to play a melody in the second staff. This was another needless difficulty when I entered the music into my notation software, because I had to double, triple, and quadruple check several staves to make sure I was following my own notes.

I mentioned at the beginning of this post that L’esprit Perdu is, in part, an exploration of my process. The points about and what I continue to describe below are all testaments to that creative exploration. The mistakes aren’t mistakes so much as they are lessons, and I’m glad to have experienced them.

After completing the handwritten draft, I began entering the music into my notation software. (I use Finale.) I made the document with the full orchestration in mind, which included 11 instruments and 15 staves. The entry took some time, given the quadruple checking - I can’t remember exactly how long it took, but I think it was around three to four weeks, in tandem with day job and personal life balance.

A huge benefit of notation software is being able to hear immediate playback - an option I don’t have with handwritten composition, other than what I can play on my MIDI keyboard. In some of my flurries of pushing the pencil, I wrote wrong notes. Thanks to playback (and just the general attention to detail to enter everything into the software), I was then able to start editing wrong notes, weird rhythms, and change any orchestration that needed to be changed.

Again, the editing time could have been cut down if I had made stronger (and smarter!) decisions early on in the process.

The first 40-ish seconds of L’esprit Perdu. Who needs time signatures anyway?

One of the defining features of ambient music is long, sustained notes and chords. I chose to tackle this by including meterless sections in the music. (Meterless meaning, in this case, music based on duration of time rather than beats per measure.) The way I wrote the meterless sections were via one-inch tick marks, with each tick representing five seconds.

A wall I knew I’d have to face in the notation entry stage was figuring out solutions to this decision, tweaking the program to show meterless sections. Through some finagling, I was able to achieve what I wanted (or close to what I wanted - “good enough for government work”).

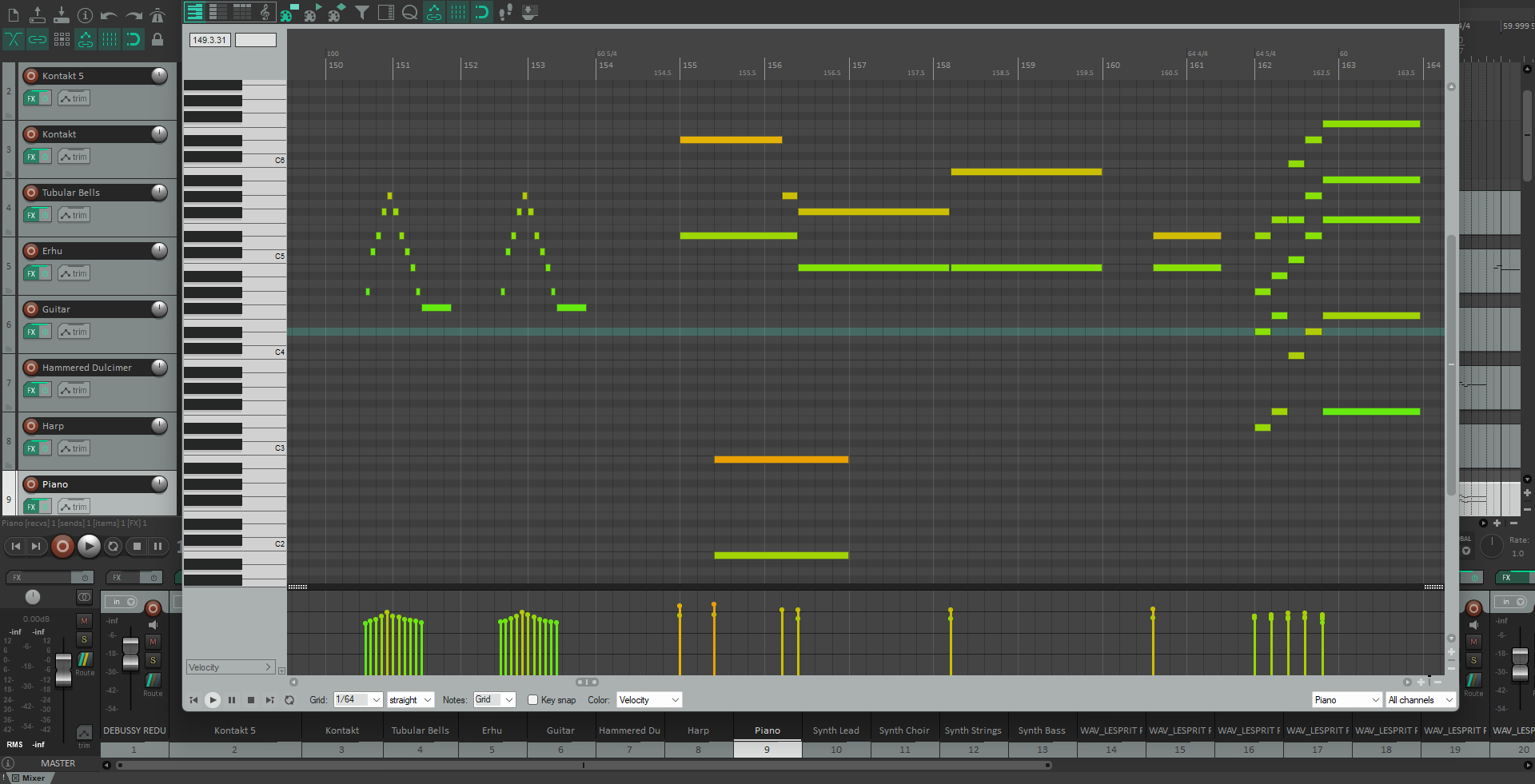

A little look at some piano MIDI.

With the notation entry complete, I was ready for the next step: exporting the MIDI information from the notation software and importing it into my Digital Audio Workstation (DAW; music production software such as ProTools, Cubase, FL Studio, Logic, and GarageBand, to name a few examples. I use Reaper and Audacity).

I could have exported a sound file from the notation software and be done sooner, which I’ve done many times in the past; however, the result would be far less professional, would have a lower quality, and would sound dated (think 90s/00s daytime TV). By completing the music in a DAW, I’m able to use virtual instruments (sampled recordings of real instruments) to make the music sound more human. This is a common technique in the film and video game industries.

Anyway, there was still a bit of editing to do at this stage. I combed through the MIDI notes for each instrument, adjusting note velocity and duration to make the music sound both natural and expressive, in the way I imagined. It’s a tedious process, but this method allows me to give myself as much control over the sound as I desire - harkening back to the topic of creative freedom.

During this stage, too, I found several moments in which the instrumentation needed adjusting: maybe a melody sounded better on dulcimer than on guitar, or maybe the piano needed to play what the harp was playing, or maybe the low bass drone needed to be cut out entirely. A lot of this happened, and I did my best to go with the flow rather than trying to be rigidly married to my existing notation. In the end, I made the decisions that felt right to me.

Finally, I moved on to mixing the instruments and adding in the sound effects. Mixing took a few days - it’s a tedious process that, admittedly, isn’t all that enjoyable to me. But it’s a critical step, so I forged ahead. I also followed a piece of sage advice: “life is an open-book test.” (I looked up some basic EQ patterns for most instruments and adjusted to taste - it saved time).

In college, I experimented with using sound effects instead of instruments in some of my compositions (like in this piece). Since then, I’ve had a fondness for this type of composition, so the last step of weaving the sound effects into L’esprit Perdu was fun. Finding just the right millisecond for a bird chirp or discovering the random placement of a rhythmic section of crickets works right in its place is a magical feeling of accomplished discovery.

Rounding Out and Wrapping Up

I mentioned at the beginning of this post that L’esprit Perdu means “The Lost Spirit” in French. Titles are difficult to create. In January, I played with different ideas for a title. With much of the melodic content pulled from Debussy’s work, I wanted the title of this piece to be in French - it felt like the right decision. Through some wordsmithing, I finally landed on The Lost Spirit - L’esprit Perdu.

And the entire piece instantly made sense to me, as though turning on a light and illuminating a dark room. The Wanderer is me; the mountainous landscape is the winding path I’ve been walking; the chiming motif is the practice of composing calling to me, and my following the sound is my readiness to return to composing; the ethereal melodies are a beckoning lure to keep following my instinct; the ending - the temple - is the relief and excitement of returning to composing after so long.

The Wanderer never gave up. He found the temple.